- 7 clarence grove

- horsforth

- leeds, LS18 4LA

- UK

- tel: 0113 258 1300

- order online

- www.editiondb.com

- info@editiondb.com

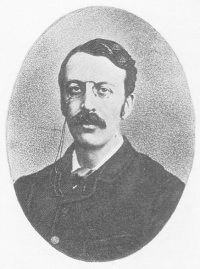

Charles Villiers Stanford (1852 - 1924)

Born and raised in Dublin, Stanford was the only son of a prosperous Protestant lawyer. As a condition of allowing him to attempt a musical career, his father insisted that he read classics at Cambridge before taking the usual course of intending musicians... in Leipzig. The young and hopeful musician obediently went to Queen's College, Cambridge and, as so many have since done, spent more time in making music than reading for his degree. In his third year he was appointed organist of Trinity and conductor of two choral societies which he combined to form the Cambridge University Musical Society, known ever since affectionately as 'CUMS'.

In 1874, still only 22, Stanford managed his third-class honours degree in classics and immediately left for Germany. After Leipzig (studying with Carl Reinecke) he studied in Berlin (with Friedrich Kiel) and travelled all over Germany and France listening to all the 'new music' of Wagner, Brahms, Meyerbeer and Offenbach. With unbridled energy he returned regularly to conduct CUMS in much contemporary music (including his own) and to begin the tradition of performing the great classical choral works (including his own edition of the Bach St Matthew Passion which remains an outstanding tribute to English musicology).

His unrivalled knowledge of contemporary music, together with his love and respect for earlier choral music, allowed him to make the biggest impact of all his colleagues in the renaissance of English music in the late 19th century. First came the church services, almost symphonic in design, with meaty organ parts which gave the kiss of life to the almost extinct English choral tradition. Then, writing for the new upsurge of amateur choirs born of the Industrial Revolution, who joined together in large 'festivals', he re-vitalised the oratorio which had been the province of the priveleged ruling classes.

At a time when few Englishmen thought much of serious music in the theatre, he wrote 10 operas on subjects ranging from The Canterbury Pilgrims to Shakespeare's Much Ado by way of the Irish comedy Shamus O'Brien and - his masterpiece - The Travelling Companion (with libretto by Newbolt, after Hans Anderson). His partsongs such as The Bluebird and Heraclitus can be sung with no unfavourable comparison beside the greatest of English madrigalists whilst among the solo songs La Belle Dame sans merci and The Fairy Lough are only two of the lyrical settings in English musical history.

Such an English genius had not been acknowledged since the days of Purcell, another great man of both theatre and church music. The musical establishment claimed him - he was both Professor of Music at Cambridge and Professor of Composition at the Royal College of Music simultaneously for nearly 40 years - and every amateur singer in the country sang his music. Above all, his students in London and Cambridge read like a roll-call of British composers of the first half of the 20th century: among those who owed much to Stanford's teaching included Benjamin, Bliss, Bridge, Howells, Holst, Ireland, Goosens, Procter-Gregg and Vaughan Williams, naming only a few. Notoriously irascible, he quarrelled with many of his contemporaries, including Elgar and Parry. He was knighted in 1902.

Stanford has often been dismissed in this century as a German imitator; an unoriginal fabricator of "Brahmsian" music. However, anything more than a cursory investigation of his music reveals his Celtic roots, as well as his intense individuality. This combining of German and Celtic traditions to create an integrated idiom was instrumental in establishing an English style upon which the next generation of British composer could build.

He composed in almost every music form including seven symphonies; ten operas; fifteen concertante works; chamber, piano, and organ pieces; and over thirty large-scale choral works. His voluminous sacred music continues to be the foundation of the Anglican tradition. He is buried next to Purcell in Westminster Abbey.

Though little of his popularity survived him, and only now sixty years later we are re-discovering his music, his influence on the British music scene of his day (approximately 1875-1915) was quite substantial. Later in his career, Stanford's symphonies were upstaged by the works of much more flamboyant orchestrators and were made to appear plain and somewhat old-fashioned in comparison with the symphonies of Elgar.

In many cases, the achievements of his own pupils in the second decade of the 20th century revealed a whole new and emerging school of English composers that tended to overshadow the later works of their mentor. However, Stanford's creative impulse and sense of invention was un-diminished in his later years and he managed to create some of his most beautiful works during this time, though many were left unpublished and few were performed.

Compositions in catalogue |

Catalogue no. |

Price £ |

To buy click PayPal links below |

Composer/arranger |

||

Chamber Music series |

||||||

Quintets |

||||||

| Fantasy for horn & string quartet | edb 0705002 |

18.00 |

C V Stanford (ed Pascoe) | |||